Handling static and media files in your Django app running on Coolify

In a previous article, I detailed my journey of hosting Django sites with Coolify, covering everything from the Dockerfile and database setup to environment variables and server configuration. It was a comprehensive guide to get a Django application up and running. However, I deliberately left out one tricky topic: handling static and media files. This aspect of deployment can be complex and certainly deserves its own article.

If your application only serves static files - the CSS, JavaScript, and images that are part of your core application - the solution is thankfully really simple: use WhiteNoise. It is, by far, the easiest way to serve static files directly from your Django application in production without needing a separate web server just for them.

However, if you’re also dealing with user-uploaded media files then you have to deal with two challenges: where to store the files and how to serve them. Let’s assume you have a standard configuration in your settings.py:

settings.pySTATIC_ROOT = BASE_DIR / "static_root"

STATIC_URL = "/static/"

MEDIA_ROOT = BASE_DIR / "media_root"

MEDIA_URL = "/media/"

The primary problem is that media files uploaded by users will be saved inside the Docker container. Because Coolify creates a fresh container from your image every time you deploy, any user-uploaded files will be permanently lost. That’s not exactly great.

A common and effective solution is to store these files on a dedicated cloud storage service, like Amazon S3 or Cloudflare R2. The excellent django-storages package makes this integration fairly straightforward. You could configure it to handle only your media files while letting WhiteNoise continue to serve your static files, or you could delegate both tasks to django-storages and remove WhiteNoise entirely.

In my case, however, I preferred to keep all my project’s files on my own server. I didn’t want to introduce a dependency on an external storage provider like S3 or R2. This choice meant I had to find a way to solve two problems: storing the media files outside the container and serving them efficiently.

Step 1: solving storage with Coolify Persistent Storage

Thankfully, the storage problem is simple to solve with a built-in Coolify feature: Persistent Storage. This allows you to map a directory on your host server to a directory inside your container.

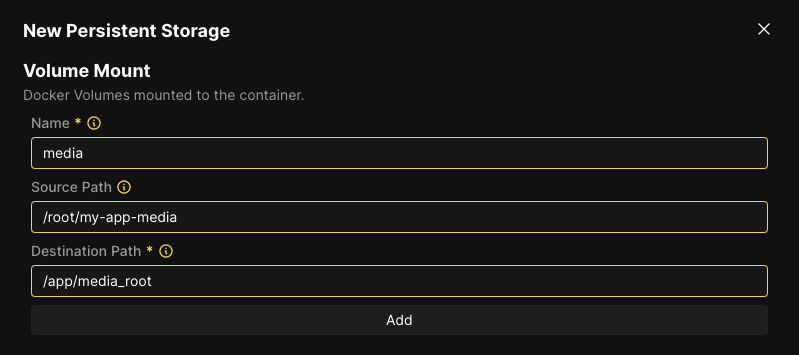

In your Django application’s resource view in Coolify, navigate to the Persistent Storage section in the sidebar and click the “Add” button. You’ll need to create a new Volume Mount with the following settings:

- Name: a descriptive name, like

media. - Source Path: an absolute path to a folder on the host server, for example

/root/my-app-media. - Destination Path: the path inside the container where your media files are stored. This should match the

MEDIA_ROOTfromsettings.py, which in our case is/app/media_root.

With this volume mount in place, all uploaded media files will be saved to the /root/my-app-media directory on the host, safely outside the ephemeral container. They will now persist across deployments.

Step 2: serving files with Caddy and supervisor

While the files are now stored safely, they aren’t being served yet. Django’s development server doesn’t run in production, and WhiteNoise is designed to handle only static files, not media files. The solution is to add a lightweight, production-ready web server to our container that will serve the media (and static) files and proxy all other requests to our Django application.

For this, we’ll use Caddy as our web server and Supervisor to manage both the Caddy and Gunicorn processes. This requires a few changes to our Dockerfile and two new configuration files. Let’s start by updating our Dockerfile. We need to install Caddy and Supervisor, copy their configuration files, and run supervisord as the main command.

Dockerfile# Use a slim Debian image as our base

# (we don't use a Python image because Python will be installed with uv)

# Set the working directory inside the container

WORKDIR /app

# Arguments needed at build-time, to be provided by Coolify

ARG DEBUG

ARG SECRET_KEY

ARG DATABASE_URL

# Install system dependencies needed by our app

RUN apt-get update && apt-get install -y \

build-essential \

curl wget \

supervisor \

caddy \

&& rm -rf /var/lib/apt/lists/*

# Install uv, the fast Python package manager

RUN curl -LsSf https://astral.sh/uv/install.sh | sh

ENV PATH="/root/.local/bin:${PATH}"

# Copy only the dependency definitions first to leverage Docker's layer caching

COPY pyproject.toml uv.lock .python-version ./

# Install Python dependencies for production

RUN uv sync --no-group dev --group prod

# Copy the rest of the application code into the container

COPY . .

# Collect the static files

RUN uv run --no-sync ./manage.py collectstatic --noinput

# Migrate the database

RUN uv run --no-sync ./manage.py migrate

EXPOSE 80

# Copy configs

COPY .config/Caddyfile /etc/caddy/Caddyfile

COPY .config/supervisord.conf /etc/supervisord.conf

# Run with supervisord

CMD ["supervisord", "-c", "/etc/supervisord.conf"]

The key changes here are installing supervisor and caddy, exposing port 80 for Caddy, and updating the CMD to launch Supervisor, which will in turn start Gunicorn and Caddy. You’ll need to update the “Ports Exposes” setting in the General Configuration tab (under “Network”) from 8000 to 80.

.config/Caddyfile:80

handle_path /static/* {

root * /app/static_root

file_server {

precompressed gzip br

}

header Cache-Control "public, max-age=31536000, immutable"

}

handle_path /media/* {

root * /app/media_root

file_server

header Cache-Control "public, max-age=86400"

}

handle {

reverse_proxy 127.0.0.1:8000 {

header_up Host {host}

header_up X-Forwarded-Proto {scheme}

header_up X-Forwarded-For {remote_host}

header_up X-Real-IP {remote_host}

header_up X-Forwarded-Host {host}

}

}

This configuration tells Caddy to serve any requests for /static/* and /media/* from their respective directories on the filesystem. All other requests are reverse-proxied to our Django application, which Gunicorn is running on 127.0.0.1:8000.

.config/supervisord.conf[supervisord]

nodaemon=true

logfile=/dev/null

logfile_maxbytes=0

logfile_backups=0

loglevel=info

[program:gunicorn]

command=uv run --no-sync gunicorn --bind 127.0.0.1:8000 --workers 3 --access-logfile - --error-logfile - --log-level info config.wsgi:application

stdout_logfile=/dev/stdout

stdout_logfile_maxbytes=0

stderr_logfile=/dev/stderr

stderr_logfile_maxbytes=0

autorestart=true

startretries=3

[program:caddy]

command=caddy run --config /etc/caddy/Caddyfile --adapter caddyfile

stdout_logfile=/dev/stdout

stdout_logfile_maxbytes=0

stderr_logfile=/dev/stderr

stderr_logfile_maxbytes=0

autorestart=true

startretries=3

Supervisor is responsible for starting and managing our two processes: Gunicorn and Caddy. It ensures that both our application server and our file server are running concurrently.

An added benefit of this supervisor is that it’s super easy to add a long running process into the mix, for example for django-tasks:

.config/supervisord.conf# ...

[program:django-tasks]

command=uv run --no-sync ./manage.py db_worker

stdout_logfile=/dev/stdout

stdout_logfile_maxbytes=0

stderr_logfile=/dev/stderr

stderr_logfile_maxbytes=0

autorestart=true

startretries=3

priority=30

Side note: you might wonder why we don’t use Docker Compose to run Django, Caddy, and the

db_workerprocess all in their own containers. We’d get separate logs which would be very nice, containers can be restarted individually, and one crashing container won’t bring down the others. Those are all really great benefits, but we’d loose rolling updates, so your app would be down for a short time every time you deploy changes. I also found that dealing with build-time environment variables was a lot more complex with Docker Compose.

Step 3: profit

With these new configurations committed to your repository, your next Coolify deploy will build a container equipped to handle everything. Caddy will efficiently serve static and media assets from the persistent volume we configured, while Gunicorn continues to handle the dynamic application logic. This setup keeps all your data on your own server, solves the ephemeral storage problem, and provides a robust, production-ready solution for serving all your Django project’s files.